After the Overdose: Life on the Edge of Survival

Excerpt:

Surviving a fentanyl overdose is not a return to normal—it’s a chemical reset with a dark pull. Unlike a cardiac arrest survivor, a person revived from fentanyl often wakes up in withdrawal, confused, and desperate to use again. This isn’t weakness—it’s neurobiology.

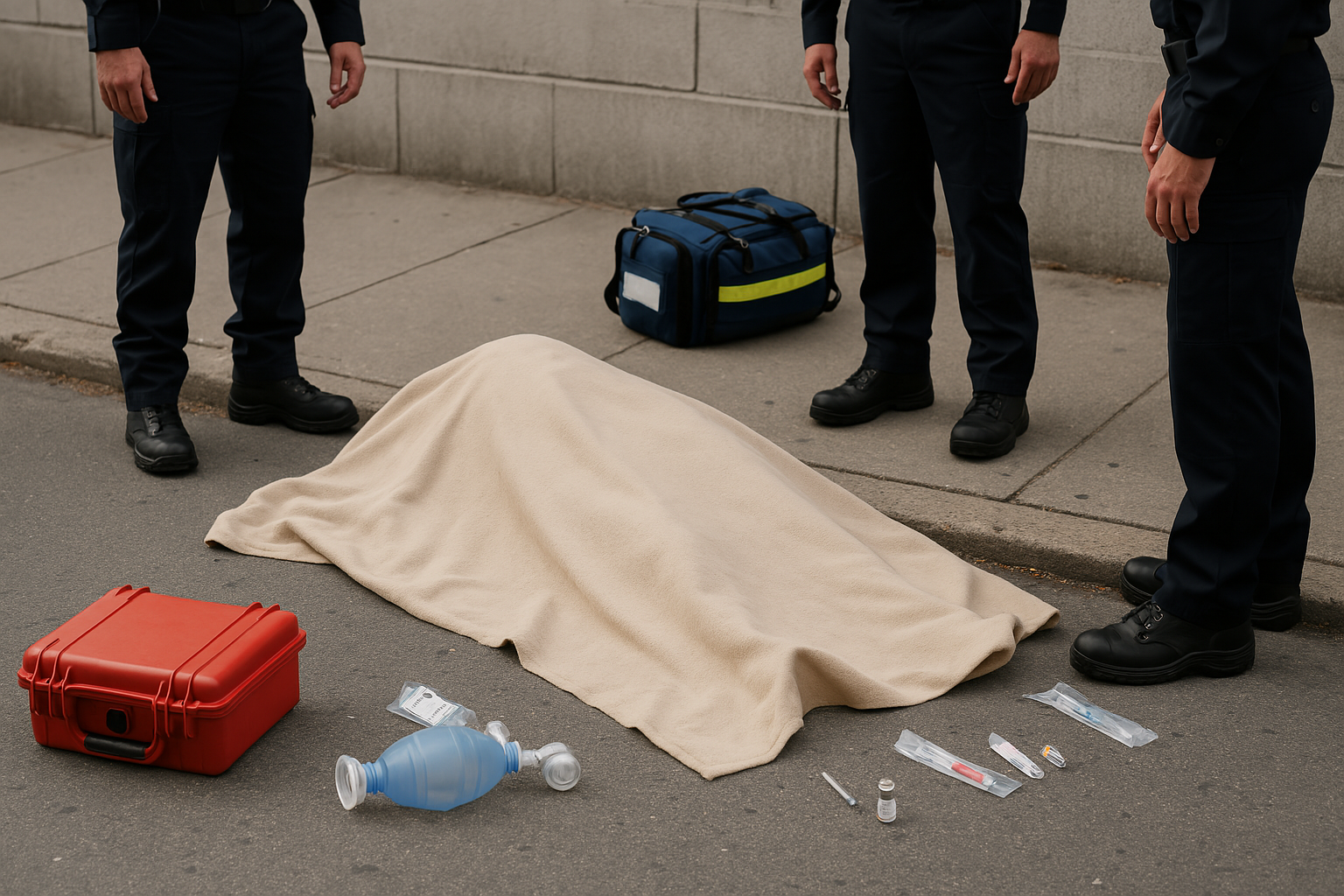

The Moment After: What Happens When Someone Survives a Fentanyl Overdose

Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine, can cause overdose in microgram amounts. When someone overdoses, their breathing slows—or stops altogether—due to central nervous system depression. Naloxone (Narcan), an opioid antagonist, can reverse this effect within minutes, often bringing someone back from the brink of death.

But surviving the overdose is not the end of the crisis. It’s the beginning of a complex, painful, and often misunderstood experience.

The Physiology of Revival: What the Body Endures

When naloxone is administered, it forcibly displaces fentanyl from the brain’s opioid receptors. This reversal is life-saving—but also abrupt and traumatic.

Within moments, the individual is jolted awake into a full-blown withdrawal: chills, vomiting, diarrhea, muscle aches, and overwhelming anxiety. Imagine your body going from a state of near-death euphoria to utter panic in 60 seconds.

This isn’t just unpleasant. It’s terrifying and destabilizing.

The Compulsion to Use Again

Here lies the great misunderstanding.

Why would someone, just saved from death, immediately seek out more fentanyl?

Because their brain, stripped of opioids, interprets the absence as pain, suffering, and danger. The relief they were chasing before the overdose has now turned into a psychological and physical crisis. Using again isn’t about getting “high”—it’s about silencing the storm.

In the same way a drowning person gasps for air, an opioid-dependent person gasps for fentanyl—not for pleasure, but for relief.

Compare to Cardiac Arrest: Two Rescues, Two Realities

When someone suffers a cardiac arrest and is revived by a defibrillator, the response is vastly different. Once stabilized, the patient is often grateful, reflective, and compliant with follow-up care. The body’s trauma does not include a neurochemical dependence screaming to be satisfied.

The cardiac arrest patient is treated with support, rest, and long-term medical oversight.

The fentanyl overdose survivor is often treated with suspicion, judgment, or left to walk out of an ER after a quick revival.

They both nearly died. But only one is punished by their own biology afterward.

The Prognosis: A Window of Opportunity

The minutes and hours after revival are critical.

Without intervention—medical, psychological, and community-based—many will return to use, often fatally. In some cases, people overdose multiple times in a week, or even in a day.

The prognosis depends on immediate access to:

- Detox and withdrawal management

- Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) like Suboxone or Methadone

- Mental health counseling

- Safe housing and community support

But too often, those things aren’t offered. Or if they are, they come with a waiting list.

Conclusion: It’s Not a Weakness—It’s Biology

We don’t blame heart attack victims for their chest pain or diabetic patients for needing insulin. Yet when someone survives a fentanyl overdose and seeks relief, society still treats them like criminals or failures.

Understanding the post-overdose experience means seeing the person behind the statistics—and recognizing that survival isn’t just about breathing again. It’s about having a reason—and the support—to keep living.